UAVs and the focus on integrated navigation systems

UAVs and the focus on integrated navigation systems

A drone, in technological terms, is an unmanned aircraft. Drones are more formally known as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or unmanned aircraft systems (UASes). Essentially, a drone is a flying robot that can be remotely controlled or fly autonomously through software-controlled flight plans in their embedded systems, working in conjunction with onboard sensors and GPS.

In this blogpost, I will display the range of piloting software onboard a drone, and then proceed to show why integrating navigation systems to drones is an appealing business model – further referred to as the ‘integrated approach’. By presenting the range of software onboard a drone, I have gained more appreciation for the technological complexity of this system. With this integrated approach, navigational software becomes a core element of a business’s drone strategy. This already exists at tech giants like Amazon or even IBM, who have full-time drone developers, i.e. engineers who dedicate themselves to building drone ‘steering’ control apps and drone applications that sit on the drone devices themselves to analyze the worlds that they fly into.

To do this, we will examine a specific kind of drone: one that must navigate an environment in real-time and avoid obstacles, as opposed to a drone with a pre-programmed path. I am especially honed on these drones because I’m set to build a drone for the Alpha Pilot autonomous drone race. Lockheed Martin is paying out $2.25 million dollars to the fastest drone in this obstacle race.

Business applications of real-time drones range from search and rescue, surveillance, traffic monitoring, weather monitoring and firefighting, to personal drones and business drone-based photography, as well as videography, agriculture and even delivery services. In the past, these drones have been manned vehicles, where the operator had a visual through a front-camera. While this still holds, human intervention means there must be a human on the other end, perhaps something that is not affordable, like in large scale logistic operations. Additionally, in support of real-time flight systems, human intervention will inevitably introduce time delays:

- for sending and receiving data, especially to transmit quality video,

- for the operator to observe (on average 200ms) and react (hopefully a trained operator)

- lets not forget data latency issues in places there isn’t a network coverage…

These are compelling arguments for software to process data and make decisions without human intervention. As a result, pioneers in drone technology have moved toward different strategies. DJI is the world’s leader in the commercial and civilian drone industry and currently covers over 70% of the drone market. Their partnership with Microsoft in 2018 speaks directly to their transition to software-based solutions. DJI’s partnership offers three distinct strategies for software-based data processing:

(1) Drone images sent to a datacenter running Microsoft Azure AI to help make decisions.

(2) Drone imagery processed on Windows running Azure IoT Edge with AI workload.

(3) Drone imagery processed directly onboard drones running Azure IoT Edge with AI workload.

In fact, I believe there are two major reasons that onboard systems are vastly superior to central datacenters (option 1) and even edge datacenters (option 2).

- Reliability: The latency that the traditional cloud computing model introduces into systems will not work for many edge applications, such as autonomous vehicles. Advancements in long-range radio technologies have cheapened IoT systems, but also introduced extremely limited communication bandwidth for transmitting data back to the user. ML-based analytics algorithms on edge IoT devices can dramatically increase information density.

- Privacy: Going back to our example of a real-time navigational drone, there is sensitive information that we don’t want exploited from the drone. No transmission of data means no exploitation of transmitted data!

The last of the three, onboard processing, has grown tremendously in the last few years. It is a new breed of software capable of processing data and making decisions without a connection. Fortunately, the smartphone revolution has helped shrink down processors while making them burlier and cheaper and more energy-efficient. Additionally, in the past six years, the amount of compute used in the largest AI training models has, on average, doubled every hundred days – contributing to a 300,000-fold increase in AI computing. As a result, in the last year [2019], there are a few products designed to run ML algorithms and inference in embedded applications. There are RISC-V microcontrollers with machine learning accelerators. Google has a custom-designed ASIC that accelerates TensorFlow. Google recently released Coral, a board with an Edge TPU platform & custom ASIC with form factor & power of a Raspberry Pi. Intel has a Neural Compute Stick for SBC. The Jetson Nano has portability & plug in product.

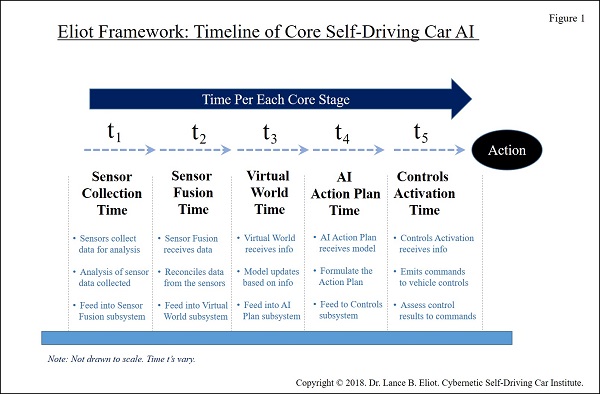

There is however a sequence of steps, from the detection of an obstacle to autonomous reactions of the drone. AI needs to systemically negotiate the environment around them before making decisions. This is how I discovered the Eliot Framework. This nice visual comes from a presentation on the AI of autonomous cars which function very similarly.

Notice that, to process images and categorise the environment around the drone, it can adopt statistical AI systems – machine learning, deep learning, deep reinforcement learning… (t_2) To create a virtual model of the environment, there is a need for a coherent VR framework (t_3). Decisions capabilities require finer data handling (t_4). And then only does this finally reattach to the conventional control theories that govern dynamics of flight (t_5). I hope this clarifies the range of software onboard the drone. On top of this, a drone must then integrate all these technologies with the more lower-level mechanics and electronics onboard the drone. Further even, each step of this sequence will have to negotiate the real-time constraints of embedded systems: power saving on a limited battery, limitations of the dynamics and kinematics of flight, down to the speed of individual computations.

In all honesty, modern AI does not seem prepared to tackle the challenges brought about by this model. For example, imagine that a drone is flying in a straight line. It suddenly detects that a bird will intercept its path. The drone can decide to arc around the bird. Now during this manoeuvre, the drone detects a collision with another bird that was previously outside its line of vision. This means the drone must choose a new path in minimal time. This constant readapting of the drone’s navigational system, in real-time based on old and new information is a challenging task. Within the Eliot framework, there is therefore a time master that serves to control the amount of time allocated to each step, and sometimes, to skip some steps entirely. With the case of the bird, if there isn’t enough time to process new information, the drone must guess the safest path possible. What is that safest path? I’ll leave you with this question, a question that stumps me too when it comes to developing our own racing drone.

I hope this has shown how an integrated approach to navigation systems, while daunting, is certainly one that is becoming profitable for UAV businesses.